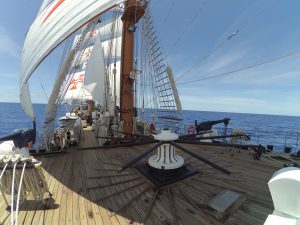

The School-Ship Sagres is currently serving as a scientific observation platform, within the scope of the SAIL project – “Space-Atmosphere-Ocean Interactions in the marine boundary Layer“. On January 5 2020, Sagres left Lisbon and started a 371-day trip around the world. However, the crew was instructed to anticipate their return to Portugal, due to the covid-19 pandemic, so the ship is expected to return in mid-May. The measurements carried out on board will ensue, not until the ship’s return to Lisbon, but also as soon as the trip restarts.

BIP INESC TEC Magazine interviewed some of the INESC TEC’s researchers who were on the ship, in order to understand the elements that lead to climate change.

SUSANA BARBOSA, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS) and the Centre for Information Systems and Computer Graphics (CSIG)

There is a set of measurements that are currently being made autonomously, namely through antennas and sensors mounted on the masts. What kind of scientific work has been carried out during the trip? What will be next steps?

There is a constant surveillance of the monitoring system on board of the Sagres, in order to identify as soon as possible any anomaly in the sensors, thus limiting the eventual loss of data. However, collecting data is not enough; evaluating the quality of the data is also essential, and that is why we developed exploratory analysis procedures for all the data collected during the trip. The continuous implementation of quality control and data management methods makes it possible to prepare all the data collected during the trip, and then upload it to the INESC TEC research data repository.

How was the relationship with the Captain and the remaining crew aboard Sagres?

The Captain played an important role in the success of SAIL ever since the beginning. He provided crucial support before the trip and during the installation of the monitoring system in Sagres, and we should point out his active collaboration in the project – namely by helping us collecting biological fish samples and sharing his knowledge about navigation and meteorology, which proved to be a quite valuable asset.

The relationship with the crew was amazing: more than welcomed, I truly felt like an “honorary member” of the Sagres garrison! All members were extremely kind, from the officers to the cadets. It was a privilege to experience the day-to-day navigation on board of Sagres, as well as other remarkable moments: the official presentation dinners, the Line Crossing ceremony (when Neptune himself comes on board while the ship crosses the Equator!) or the celebration of Sagres’ birthday on February 8 (with the first glimpse of the Brazilian coast).

CARLOS ALMEIDA, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS)

Before departing, you had to equip the School-Ship Sagres with all the technology required to carry out the project. What were the main challenges of this task?

The period before the departure of the Sagres as a true race against time, in order to make sure everything was ready and running smoothly – after all, this was going to be a one-year mission, and we were going to collect data on a regular basis. We had to select and acquire the sensors, the computer systems and all the hardware necessary for the installation, and we carried out a pre-installation project in the laboratory, even before we got said equipment.

The biggest challenges were, on the one hand, adapting the sensors so we could mount them on limited and elevated spaces (25 meters), namely the mizzenmast, as well as adjusting some of these sensors for maritime environments, so they could operate for longer periods. On the other hand, we had to develop computer applications capable of recording data in a continuous and very reliable way – Nuno Dias and António Ferreira did an excellent job in this task.

Another great challenge – that was particular interesting for me – was the development of a system based on a robotic platform, capable of recording data under water. This device called tow-fish was developed from scratch at CRAS, and tested for the first time at Sagres, between Tenerife and Cape Verde, the second stage of the mission. The tow-fish has a computer system on board that records data from 12 different sensors, later copying said date to the file management system installed on the ship. There is a permanent fibre-optic communication with the tow-fish, which allows us to see the data in real time. At the time of this interview, the tow-fish (towed at a distance of 120 meters) was in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean and en route to Cape Town, recording data for 15 consecutive days.

Records show that Carlos climbed onto the ship’s masts to clean and maintain the project’s sensors. Did the trip make you contact with your “inner sailor”? Did you acquire “new tastes”?

I have always had a very strong connection with the sea and I love to sail. Due to its beauty, size and relevance, the School-Ship Sagres can actually “spark” the sailor inside us, even among those who never had a close relationship with the sea. During the installation of the equipment, I went up the mizzenmast several times. Initially, one can only experience a deep feeling of reverence and astonishment for the view up there. However, we get used to it, and not even the ship’s swaying can bother us. During the trip between Rio de Janeiro and Montevideo I had the privilege to climb the royal mast (yes, this is the name of the tallest mast on the ship, with 40 meters). The feeling is overwhelming, and no photograph or video can ever do it justice… It’s freedom, it’s the vastness of the sea, it’s peace… it’s incredible. I really hope to get a chance to climb the only mast I have not climbed yet – the foresail.

NUNO DIAS, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS)

As “pioneers” (first researchers to embark) on this adventure, what “tips” did you leave to the INESC TEC teams that were succeeding you?

Since we were the first ones to embark, we immediately faced additional challenges. We spent the trip between Lisbon and Tenerife without having any contact with our families or INESC TEC, unable to report how the mission was going. There were no Internet or telephone connections. At Tenerife, INESC TEC provided a satellite phone for the researchers, which allowed us to communicate at any time (in addition, the ship’s technical staff managed to install the Internet on board – even if limited). The recommendations we gave to the following staff were essentially on how a military ship works.

For instance, there are stairs reserved to the Captain (portside stairs); we had to comply with the lunch and dinner schedules, since the Captain and the first officer did not sat down while the visitors (we) were present; one could only have access to the officers’ areas with a prior authorisation; there were two chairs in the officers’ mess that could only be used by the Captain and the first officer. Obviously, we only learned this (nobody explained it to us!) because we broke all the rules during the first days on board – we were even reprimanded by the officers!

Then, we provided tips on how to manage the computational aspects of the system and how to solve problems that could eventually occur. Now, almost everything is automated and the intervention is almost null! Only the tow-fish requires some sort of intervention – you have to put it in/pull it out of the water at the Captain’s command!

How did your work contribute to the project?

I was mainly involved in the installation of different software, developed for registering the sensor data, synchronising it with the time-period of the measurements and carrying out the data-backup to a dedicated storage system. In addition, I developed a tool for monitoring the global status of the entire system. This tool can be by us and by the officers on board, but it can also be used remotely. Every day, I access the ship remotely and check if everything is working as it should. It allows me to collect important data and distribute the charts of the previous 24 hours.

ANTÓNIO FERREIRA, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS)

As “pioneers” (first researchers to embark) on this adventure, what “tips” did you leave to the INESC TEC teams that were succeeding you?

We provided some guidelines related to the SAIL system installed on board, as well as some tips on the protocols one should comply with while living in the ship. Since the departure from Lisbon was a bit chaotic, we were not introduced to the rules we should follow. We only discovered them afterwards… after making several mistakes!

One of the funniest situations happened in the officers’ mess, where they had their meals. In addition to the dining table, there was also a small living space, with a few chairs and a coffee table. It so happens that, one of the days, Captain Maurício Camilo entered the room and found me sitting inadvertently in his place. When he warned me about it, I got up immediately and moved to another chair… the first officer’s chair. I realised I was breaking another rule when said officer entered and claimed his place.

We also failed to comply with another rule, which prevented us from accessing the deck from the portside – said access was reserved for the Captain. Other mistakes included accessing the deck without asking the officer, or accessing the bow without asking the lookouts, who are responsible for monitoring the ocean from the prow, 24/7.

How did your work contribute to the project?

I was in charge of the tracking system, which involves multiple GPS antennas and inertial sensors. The main goal was to determine, with great precision, the global position of the ship, as well as its orientation in 3D space. This information was crucial for the adequate georeferencing of the data collected by the other sensors. The GPS system also provided time references for the purpose of clock synchronisation in the computers and the sensors. I also established a synchronisation network, which guaranteed a time base common to all systems, so that the data from the different sensors were consistently labelled according to certain periods.

GUILHERME AMARAL SILVA, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS)

Was there a daily routine on board, like in the Navy?

Yes! With the exception of graduation ceremonies, we complied with the crew’s daily routine. The reveille was at 7AM. Every day, corporal Santos would play a song (always the same song) with a bugle, which we could hear through the ship’s audio system. Breakfast was served immediately after, while lunch was served at 11:15AM. As civilians, we could choose whether to sit at the second or first tables. As Captain’s guests, we rarely chose the first. Dinner was served at 7PM. Apart from meal times, there wasn’t any pre-established routine. Each day was different, and everything depended on the sea and weather conditions. Whenever necessary, the crew had to raise/lower sails or change the position/rotation of the halyards.

When you were not working, how did you spend your time on the ship? Was it possible to have moments of leisure?

The trip was long and with excellent sea conditions! There were no major problems disrupting the stability of our systems, so we did have some free time for leisure activities. Despite not having many options, we spent our free time playing sports, watching movies, playing videogames with other officers, talking to the crew or simply admiring the beauty of the open sea.

Eduardo Silva, researcher at the Centre for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CRAS), is responsible for the technical coordination of the SAIL project, while Susana Barbosa is in charge of the scientific coordination. Luís Lima, researcher at CRAS, also participates in the project, in addition to the coordinators and those interviewed for this news piece.

The Navy/MDN (CINAV), the AIR Center (Atlantic International Research Centre), the CIIMAR (Interdisciplinary Centre of Marine and Environmental Research) and the University of Minho are the main partners of the SAIL project. The University of Reading, the Federal University of Paraná and INESC P&D Brazil also collaborate with the project.

The researchers mentioned in this news piece are associated with INESC TEC and P.Porto/ISEP.

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!