Who remembers the incredible dress worn by Cinderella? Or that iconic glass slipper? Production time: two minutes. Actual time of use: two to three hours during the royal ball. (do not be unfair – it was the Ball of the Century!)

For decades, the textile sector followed Cinderella’s formula: fast, seemingly limitless, paying little attention to what comes after. Today, the textile sector is one of the most polluting in the world, but also one of those facing the greatest regulatory, technological and social pressure to transform itself. Global fibre production reached record levels in 2024, with around 132 million tonnes of textile fibres produced. If the trend continues, this output could reach 160 million tonnes in 2030. In the European Union, in 2022, each citizen bought on average 19 kg of clothing and generated about 16 kg of textile waste. The fate of the vast majority is well known: incineration or landfill. Globally, textile recycling rates remain extremely low, with only 1% of textiles being turned into new textiles.

Faced with this scenario, the European Union’s Waste Framework Directive requires Member States to implement collection and sorting systems for used textiles and textile waste, as well as measures like ecodesign and the digital product passport. The goal is clear: textile products – and, progressively, footwear – must be more durable, recyclable and largely produced from recycled material[1]. Today, we want Cinderella’s first dress: the one sewn together from forgotten fabric scraps and worthless ribbons. It was not perfect, nor magical, but it was functional and reused what was already available.

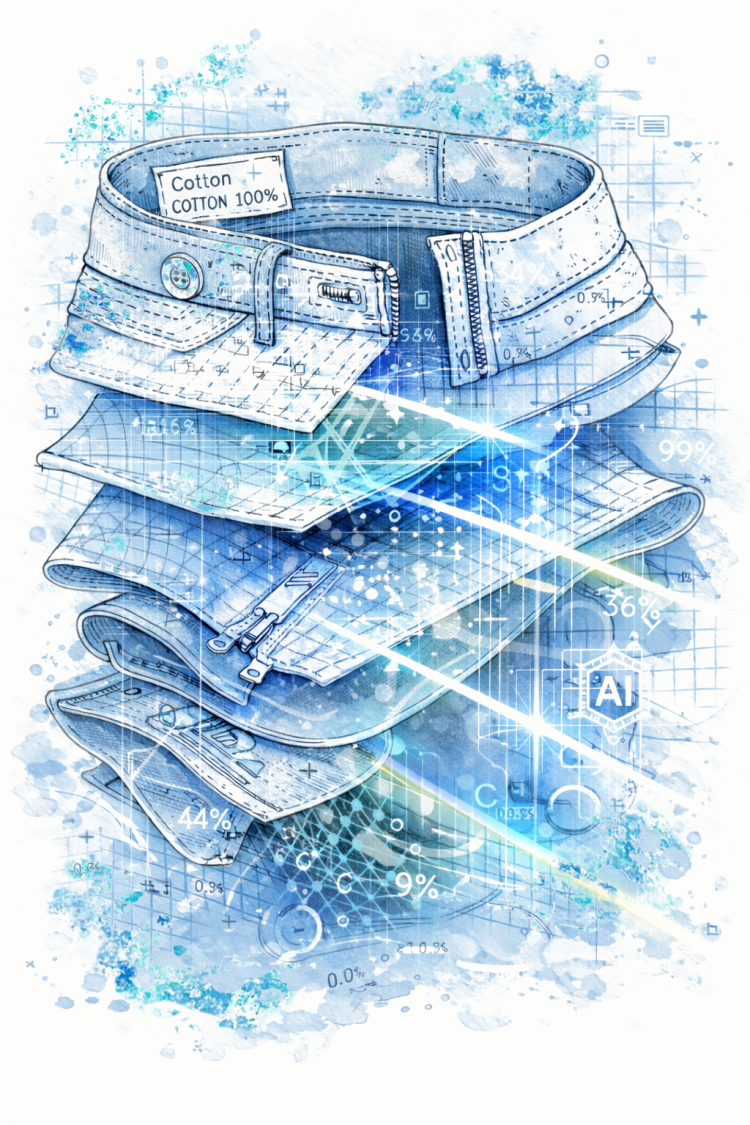

For circularity to be possible at industrial scale, it is essential to know exactly which materials make up each item and how to separate them. To sew this new Cinderella dress, we need the priceless help of the “little mice”. This is where INESC TEC comes in: through robotics, Artificial Intelligence and computer vision, the institution aims to transform the future of the textile sector.

The establishment of the new European legislation on textile waste has accelerated a transformation that had long been announced, but for which there are still no fully consolidated answers. Several barriers have been identified, ranging from inadequate collection and sorting infrastructures to inefficient manual fibre classification. In addition, both industry and consumers have yet to build robust markets for recycled products.

INESC TEC’s research has been positioning itself in this gap between legal obligation and technological maturity, as stated by researcher Marcelo Petry: “The collection of post‑consumer textiles has already begun, but from a technological standpoint there is still no well‑defined and commercially viable process to deal with these materials. Our work focuses on helping companies and society deal with this problem, which is critical from both an ecological and an economic point of view.”

Marcelo is joined by researchers Hélio Mendonça, Tony Ferreira and Daniel Lopes, who confirm the scarcity of real alternatives for textile waste and for promoting circularity. Projects such as Waste2BioComp, TexTended, be@t and Textp@ct – with INESC TEC playing an active role – seek to advance two major goals: recycling fibres and removing polluting substances associated with textile manufacturing.

The hidden DNA of fabrics: identify to separate

One of the first major challenges is precisely to think about textiles from a recycling perspective. For circularity to be possible, it is essential to correctly identify the fibres that make up each garment and separate them appropriately. “Each fibre can have different components, and recycling processes, whether chemical or mechanical, are often incompatible with one another when several fibres coexist in the same garment,” mentioned researcher Tony Ferreira. A critical example is elastane: although it is usually present in very low percentages, it is enough to compromise the entire recycling or reuse process of the fibres.

Labels do not solve the identification problem, since some garments arrive without labels and others contain incorrect information. Marcelo Petry provided some good examples: “items whose total of indicated percentages exceeded 100%, or fabrics labelled as 100% cotton which, after chemical analysis, turned out to have only 50 or 60%, with the remainder made up of synthetic, petroleum‑derived materials.”

Hence, the importance of tech‑based identification systems; and this is where Cinderella’s faithful helpers can make the difference. But how?

INESC TEC uses hyperspectral imaging technology, employing line‑scan cameras that capture detailed information from sections of fabric as samples move along a conveyor belt. “Each type of fabric has a different spectral behaviour. Based on this information and using AI and machine learning, we can identify whether a scrap is cotton, wool, polyester, viscose or another fibre,” explained Hélio Mendonça.

Nowadays, researchers work mainly with fibres such as cotton, wool, elastane, viscose, polyester, lyocell, linen, polyamide and acrylic – selected based on market studies that identify the most common and most relevant fibres for circularity. “There are many other fibres, but our goal is to address those that actually dominate the market,” said Tony Ferreira, stressing that rarer fibres such as silk are outside the present priorities.

Once the fibres have been identified, the sorting of fabrics is carried out using air jets positioned along the line to ensure that each identified piece is directed to the correct container.

This system targets textile recycling companies, but also other stakeholders in the value chain that require accurate sorting before moving on to mechanical, physical or chemical processes. It is already being tested in a more mature phase within the scope of the be@t project, through an industrial pilot for automatic sorting of whole garments in collaboration with sector partners. “Commercial systems can identify, at most, two fibres per sample,” explained Marcelo Petry. “Our system does not have that limitation: we are able to identify and quantify three, four or more fibres present in the same fabric.”

However, there are technological limits; a single coat, for example, can generate fragments of very different fabrics. “In multilayer garments, vision systems can only identify the outermost fabric,” said Marcelo. Yet, working only with scraps, at industrial level, is a more time‑consuming approach and rules out the possibility of directly reusing the fabric.

For fully industrial application, it will be necessary to increase speeds and volumes. By automating separation processes, the cost of recycling will decrease, and it will be easier to meet the legal obligations imposed by the European Union.

Before recycling, some elements must go

Beyond fibre identification, there is another significant obstacle to textile recycling: the presence of non‑recyclable accessories like buttons, zips or labels. Currently, much of this work is done manually in the industry, item by item, which severely limits scale and increases costs. But researcher Daniel Lopes has a solution that combines AI and robotics. “We are working on the automatic detection of these elements before recycling. The approach is based on high‑resolution RGB cameras, which are more accessible and scalable than alternatives such as X‑rays.”

The process begins with the garment already stretched out on a surface; then, a robotic arm carries it to the detection system, where algorithms identify the exact location of the accessories. This information is then sent to an industrial cutting machine, which automatically removes these elements. “First, we try to identify visible accessories. Then we infer areas where they are likely to exist, based on the type of garment. For example, where the zip of a pair of trousers or the buttons of a shirt would be,” described Daniel Lopes. After cutting, robotic systems remove the accessories and separate the fabric, which can then go on to recycling or reuse.

INESC TEC’s work in this field also extends to other projects, such as the automation of t‑shirt hem sewing using robotic arms. This is yet another example of how technology can transform traditionally manual processes and bring the textile sector closer to a more efficient, sustainable and circular model.

The magic is in the materials too

The path towards a more sustainable sector is not linear, nor does it depend solely on technology applied to sorting and recycling. The development of natural fibres such as hemp, wool and organic cotton offers an alternative to synthetic fibres, which have a higher environmental impact. “Innovations in dyeing processes, which currently consume large volumes of water and generate toxic waste, are also crucial. The use of natural dyes or waterless processes can reduce impact,” clarified Marcelo Petry.

The Waste2BioComp project spans fields such as textiles, footwear and packaging, seeking to replace fossil‑based raw materials with biodegradable materials that are more sustainable and meet the principles of the circular economy. “Currently, only about 9% of materials are truly recycled. The substitution of raw materials can help improve this situation,” explained Hélio Mendonça.

INESC TEC has developed an innovative robotic printing system for non‑flat surfaces, using bio‑based inks. “We used a robotic arm that holds the trainer and moves it underneath a print head. The innovation lies not so much in the inkjet printing itself, but in printing on a three‑dimensional, non‑flat item with biodegradable inks, ensuring exact synchronisation between motion control and the print engine,” said the researcher.

Handling flexible materials is, moreover, one of the major challenges in textile‑sector recycling. “Industrial robotics is used to dealing with rigid objects. A fabric behaves unpredictably: it falls, folds, and reacts differently depending on composition. Automatically stretching out a garment, especially complex items such as shirts or trousers, is still something no robot can do as efficiently as a human,” explained Marcelo Petry.

The team acknowledged that this is one of the major future challenges for robotics applied to textiles: being able to pick up a pile of clothes, remove just one garment, spread it out correctly and keep it in that position throughout the process.

The ideal dress still follows the 3 Rs

The future lies in making these technologies standard in the textile industry. “When they cease to be the exception and become the rule, the process becomes smoother, cheaper and more sustainable. The expectation is that, by automating processes that are currently manual and costly, these technologies will help increase the amount of recycled material available on the market and, consequently, reduce costs,” said Daniel Lopes.

Marcelo Petry presented an ambitious vision of industrial circularity, drawing a parallel with other sectors. “Ideally, the same factory that produces a garment should be able to receive it at the end of the life cycle and treat it properly. We are working with companies that want to recover critical raw materials from end‑of‑life electric motors. In textiles, the principle can be the same: closing the loop within the industry itself.”

Sorting, separation and recycling of textiles are fundamental to reducing this sector’s carbon footprint, but there are other issues that must also be addressed. In addition to recycling, the researchers highlighted two more essential areas: reducing excessive consumption and investing in biodegradable materials whenever possible.

“Changing consumption habits, for example, is essential to reduce demand for new products, encouraging practices such as conscious purchasing and the use of durable or second‑hand garments,” explained Marcelo Petry.

It is also important to rethink how clothes are designed to avoid material waste and make recycling at the end of a garment’s life easier, as well as to create efficient systems for collecting used clothing and promoting the circular economy. Only by addressing these multiple questions will we be able to significantly reduce the carbon footprint and make the textile sector more sustainable.

Research does not provide “miracle solutions”, but it does build the foundations needed for change. From Hélio Mendonça’s perspective, companies will inevitably have to adapt, and the technological solutions developed at INESC TEC have a promising future ahead. “There is no single answer. There is a set of technologies, approaches and decisions that must be combined; and I am optimistic – time is against us, but when something becomes compulsory, change eventually happens.”

In Cinderella’s story, a single spell from the fairy godmother was enough to create a dress; but much more is required in the real world. At INESC TEC, magic gives way to technology to transform the textile sector. (shhhh… this time you can stay after midnight. Bibidi-Bobidi-Boo!)

[1] For a more comprehensive analysis, please check the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles

The researchers mentioned in this edition of SPOTLIGHT are associated with INESC TEC and the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto.

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!