There are many memories in José Nuno Oliveira’s office. As a professor and a researcher, he has spent over 40 years moving between the laboratory and the lecture hall. In Braga, he joined a group of restless minds overflowing with ideas finding a “sense of purpose” through their connection with INESC.

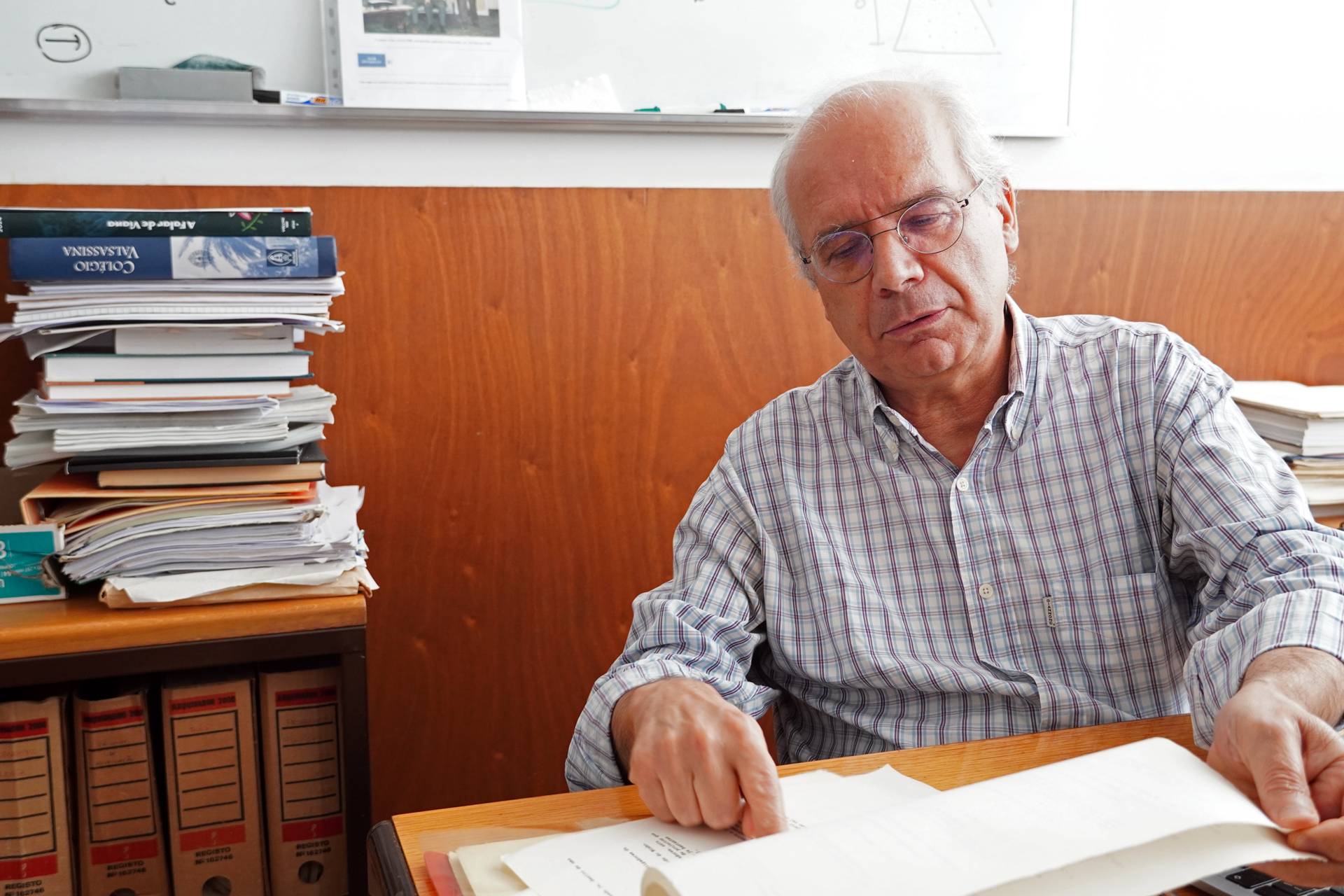

José Nuno Oliveira plays many roles, but in his “next life” he says he’d be happy as an archivist. As that didn’t happen in this one, he stores much of the institution’s trace and historical memories in his office: there are stacked cardboard boxes, catalogued folders, and reams of paper taking up a good part of a sunlit, spacious room. One folder bears the title: “Centre for Systems Science and Engineering, meeting of the Computer Science Group”, taking place around 10:30 a.m., at the “kitchen at D. Pedro V”– one of the buildings used by the University of Minho in 1984, before settling in Gualtar.

José was there; having returned from the University of Manchester with a master’s and PhD, he joined a teeming group. In that kitchen, people were “trying to find a sense of purpose”, looking for solid ground to take confident steps. It’s all documented in the hundreds of pages written by colleague and friend José Manuel Valença, who recorded those meetings in a space that served “more intellectual than culinary purposes”. There was enthusiasm; they were seeking “critical mass”, but from their “Gaulish village” perspective, the rest of the country seemed far away. It was INESC that channelled the motivation of this handful of researchers and lecturers – this is the story of a connection that was born twice: it had “two embodiments”, as José Nuno Oliveira summed up.

But there would have been no kitchen without mathematics. Before INESC existed, in the 1970s, he fell in love with this subject, but he decided to study Electrical Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto (FEUP). In 1978, he began a career full of sums: one week after finishing his degree, he found himself in Minho, preparing classes during the summer. In 1980, he travelled to England pursuing studies in computation theory under a fast-track training programme. Within this “triangle” of Porto, Braga, and Manchester, he built a research and teaching career that spans more than four decades.

“When I started, I learned many things, but above all, I learned (in those years in Porto) a sense of thoroughness. That is, to understand mathematics as providing an essential service. Mathematics is the way we predict the behaviour of what we’re going to build as engineers – the quality and reliability stem directly from that,” he explained. And that fits perfectly with someone who “likes to make things” – but not “in any old way”.

When everything was more “lightweight”

Still in England, he became involved in the study of formal methods, used to design high-quality software with guarantees of correctness, he perceives himself as a “researcher and lecturer”, and finds his sense of purpose in the lab and the classroom. With little interest in bureaucracy, he was fortunate to find “helmsmen” like José Manuel Valença, who led a group that did far more than sit around the table (kitchen or otherwise) to discuss what to do. Back then, in Braga, they were fighting for pedagogical recognition, creating a new course and new curricula to break away from the “closed-minded” academic landscape of the time. There was no fear – “there is more now”, he mentioned – but rather a diligent innocence.

“We were engaged in science in a very different way; we didn’t publish anything, but we learned at an incredible pace. Today, there’s a lot of bureaucracy in science, whereas back then everything was much more lightweight.” By way of example: “nowadays, you need to submit project proposals and prepare a Plan B in case something goes wrong; we didn’t care about any of that. We were just waiting for an opportunity to put into practice what we taught students in class – the use of formal methods,” José recalled.

That’s where INESC comes into this story; José Nuno Oliveira rarely misses a date in this narrative and is quick to find the minutes or document that proves what he’s saying: “luckily, as I have plans to set up an archive, I’ve got everything organised – more or less”. He traced a note with his finger, regarding a meeting in Lisbon, in 1987: “this was the start of our connection to INESC”, a “very interesting” period, which lasted until the mid-1990s.

An urgent message and a stop in Luso

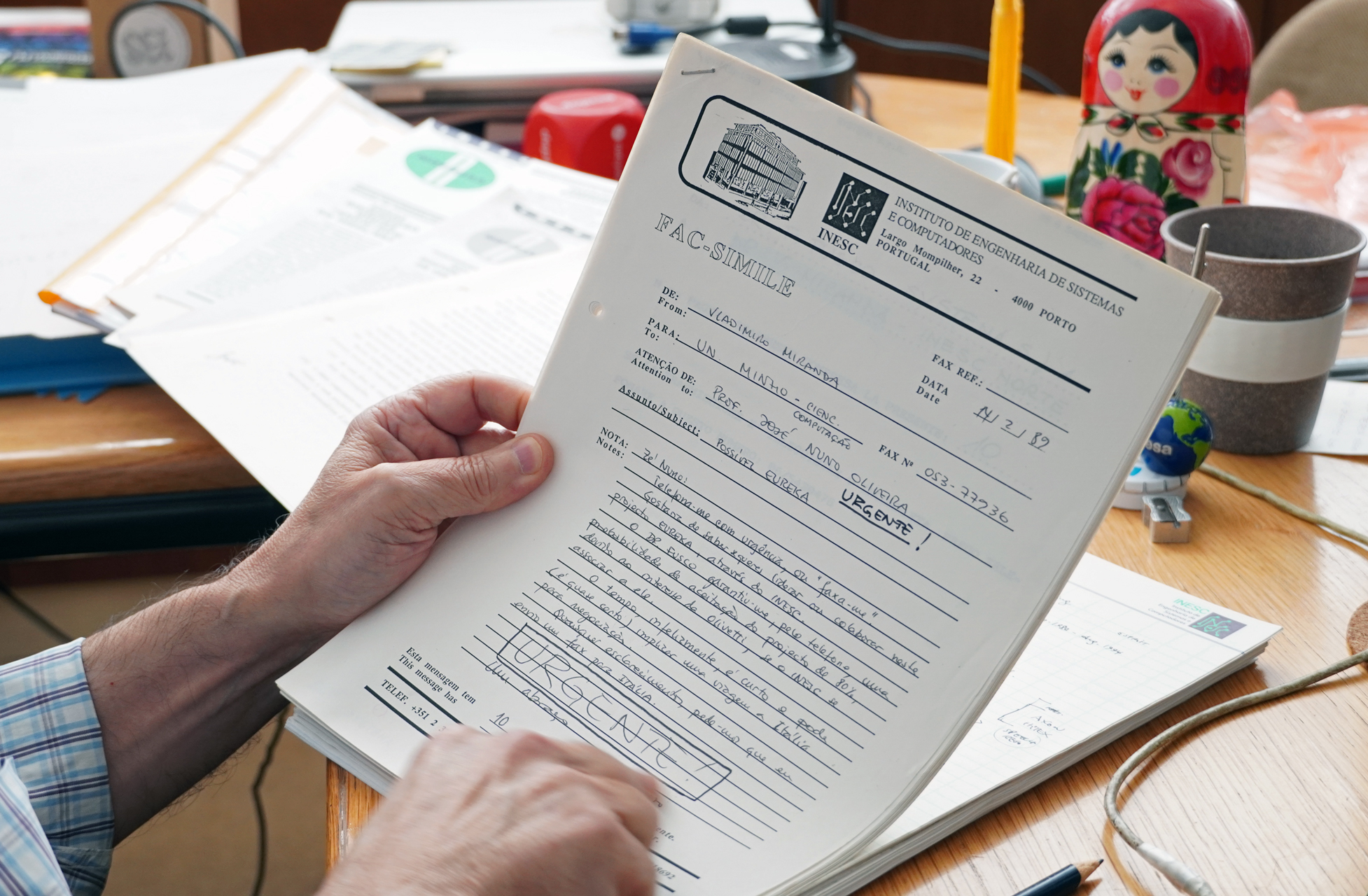

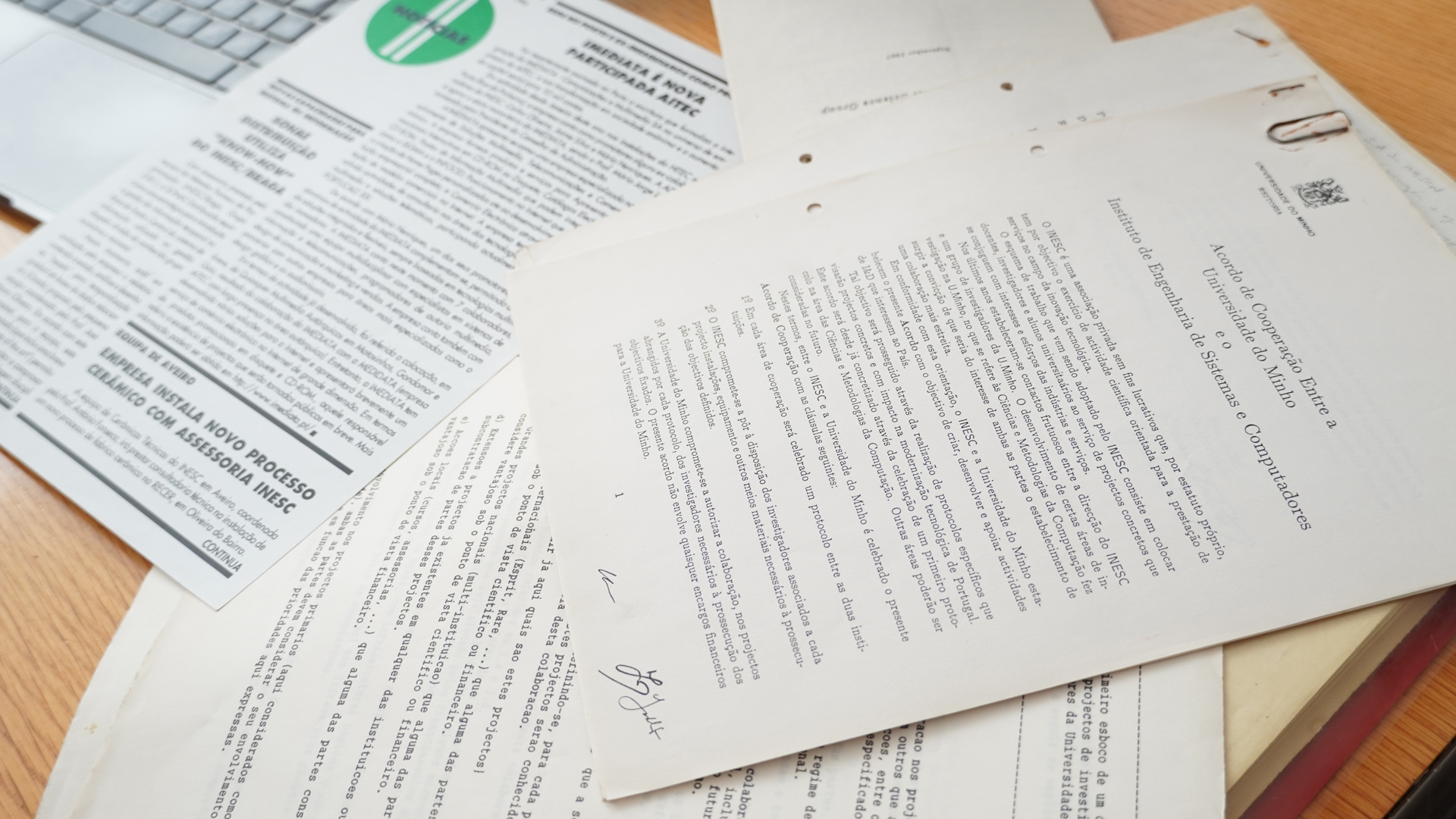

The formal agreement came in 1989, following a “strategic stop” in Luso at a gathering of various INESC groups; the meeting at INESC Lisbon – involving Lourenço Fernandes, José Manuel Valença, and Amílcar Sernadas (who led a group in the capital committed to introducing similar reasoning techniques into programming) – secured the future “Braga team” a ticket into the INESC universe. Only the signature was missing, but as José Nuno Oliveira once wrote, “reality had already anticipated formality” – this time, via fax.

He held it in his hand; from Largo do Mompilher, Professor Vladimiro Miranda sent an “URGENT!” message (written in capital letters) by fax to the team of Computer Science at the University of Minho; José started to read the copy: “Zé Nuno, call me urgently or fax me.” The reason? To find out if there was interest in participating, “via INESC”, in a Eureka project with Italy’s Olivetti. “It was what we’d been waiting for all that time – the right opportunity to test what we believed in.” Trips to Porto became more frequent, and he still fondly remembers the “kindness” of Regina Freitas, the person he most associates with INESC Porto, and who used to welcome him.

In this first “materialisation” of the Braga-INESC connection, the Eureka project flung open the doors for a group that believed in a computer engineering entirely rooted in mathematics to grow. “We thrived in this ecosystem; big opportunities are created through institutes like INESC. In my case, this connection to industry helped me become a better teacher, to teach with more confidence.” And more than that: the connection also served to reinforce the conviction that the ideas developed by that group north of Porto were sound. “Because teaching in class is one thing, applying it is another; it’s when you step into the field and score points precisely because you thought that way. And thankfully, I have many such examples.”

A laboratory and high-assurance people

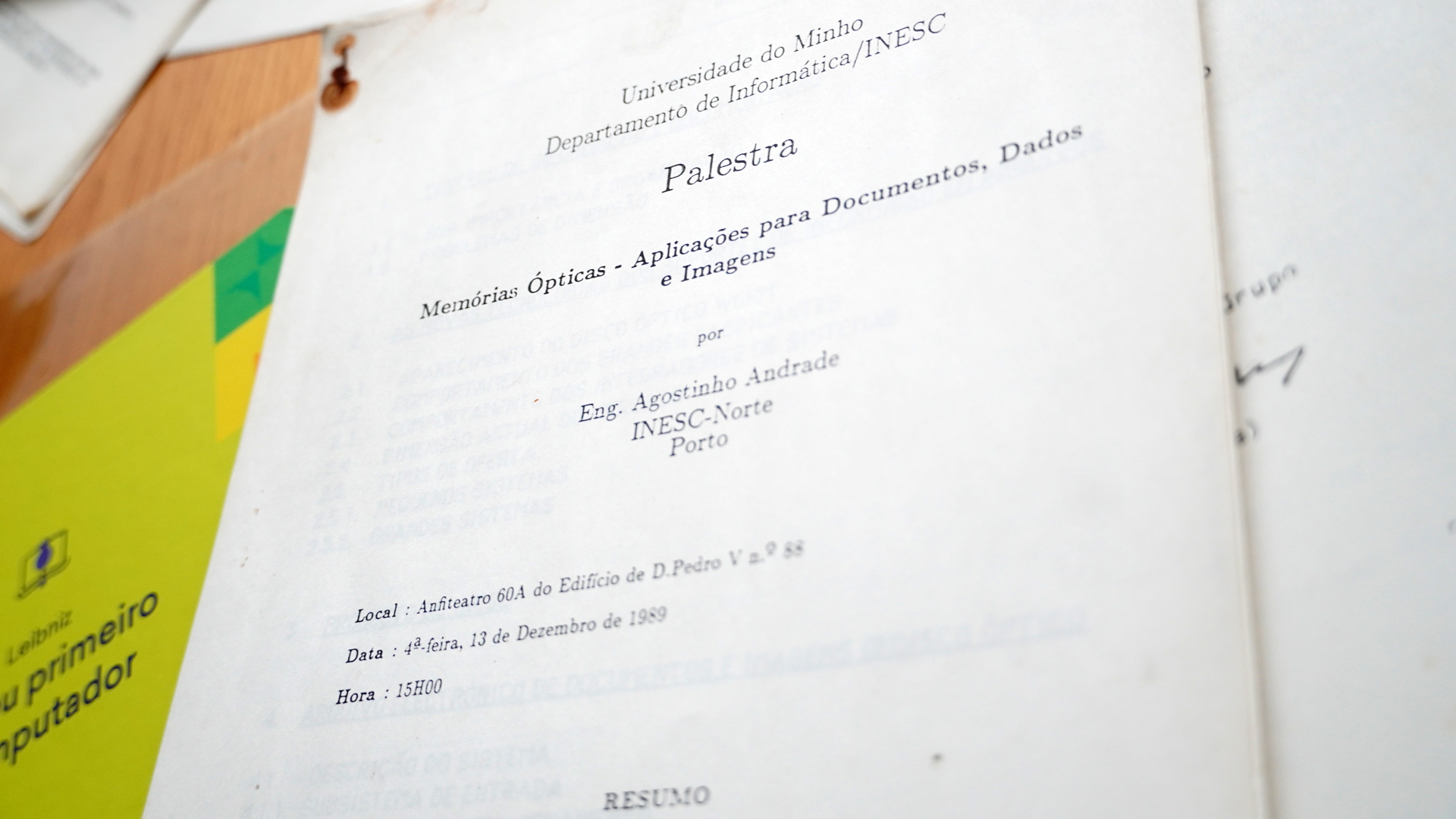

Alongside those carefully preserved examples are clues to the “second materialisation” of Braga’s link to INESC – this time, with INESC TEC. Between 1989 and 2012, when a collaboration protocol was signed, the formal connection had waned, and the reconnection occurred with the creation of the High-Assurance Software Laboratory (HASLAB), one of INESC TEC’s decentralised research units. More recently, both institutions signed an agreement to formalise INESC TEC’s hub at the University of Minho.

Ever loyal to calculation and formal methods, he admitted that working with pencil and paper isn’t the most glamorous side of computer science. However, the “impact” of the areas involving the 150+ researchers associated with HASLAB is “significant”. José Nuno added, with a smile, that computer scientists prefer being “at the piano”. “People sometimes think that only when your fingers are on the keyboard are you programming. No: you must think a program through. And there are techniques for thinking programs, which we must teach.”

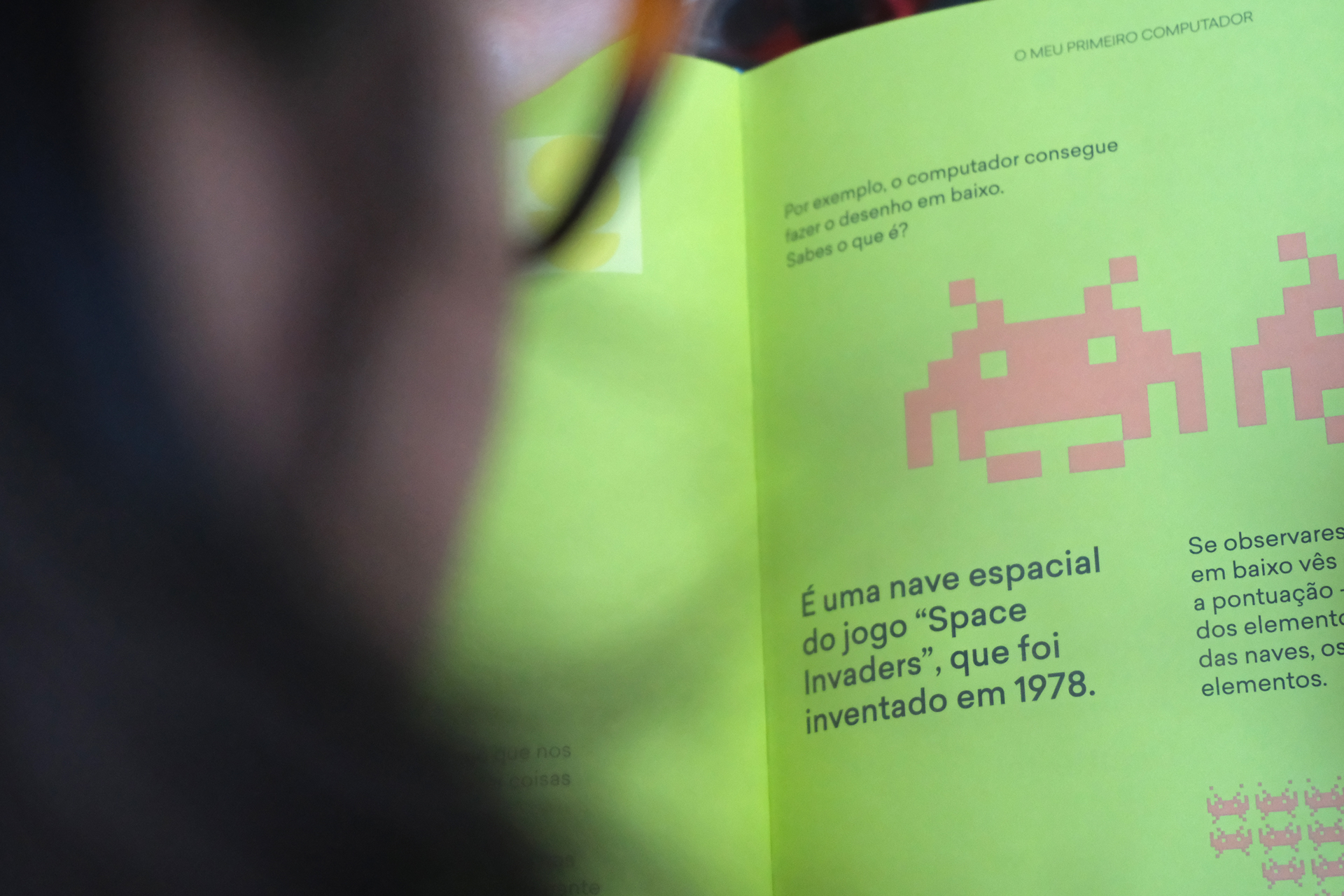

That’s also what he emphasises in the classrooms, the stages where he feels at home. He’ll still add a few more lectures to the thousands he’s already given. Retirement may be near, but he’s “completely available to continue teaching” – there’s no better way, he said, to know if we really understand what we think we know. Maybe that’s why he recently joined a project with ENSICO association, aimed at introducing the binary world of computing to younger students. “It starts in the very first degree, and we adopt the principle that computing can be learned without computers.” The true testing is done with paper and pen.

“The Braga crowd is doing well” – and proudly so

It wasn’t at the academic halls of Braga, in 1978, that he first stepped onto a “stage”. While pursuing his degree in Electrical Engineering, he practiced with the strings of an instrument that demands attention, as a student at the Porto Music School. That’s where he gave his first (evening) music theory lessons to help fund his studies, an experience that gave him the confidence and versatility for a path marked by both questions and answers.

Music has always stayed close. And while it may no longer intersect with the classroom, there’s always been space for it outside it. For now, he limits himself to “tuning” the violin, but his passion for music continues. After the lab and the university, it’s in nature that he finds peace.

His plan is to stay well-grounded in this trifecta: nature, university, and music. As he moves within it, he documents – a “frustrated archivist”, as he calls himself – much of the story of how a university and an interface institute tackled the natural “obstacles” of a shared journey. In the future, he’d like to further organise the archive that shows how an institute, a university, and all those involved in their orbit helped modernise the country. Maybe he’ll organise an exhibition to show that “the Braga crowd is doing well”, and is “very satisfied with the relationship” with INESC TEC.

“The documents show that this journey was built by many people – many of whom made this connection happen. I was lucky to work with them, and that they allowed me to “invest” in the classroom and in the lab. We got here – to a great institute and a great university – because of them. An organisation that doesn’t know its own history also doesn’t know its nature or worth. Even if that history contains mistakes,” he stressed.

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!