In Christopher Nolan’s not so distant future, schools focus on educating farmers rather than engineers. The planet struggles to feed millions of people, since the climate no longer cooperates with the agriculture practices carried out for centuries. In many ways, Interstellar depicts a scenario that, decade after decade, is becoming like our reality.

Even if future climate agreements are fulfilled, there are still inevitable consequences. The sea level will rise and we expect the occurrence of extreme weather events like floods and droughts. Said events will influence the habitats of thousands of species and the way they feed – including humans. The FAO estimates that we must increase food production up to 70% in order to feed the world’s population in 2050. These are high figures, and somewhat unattainable, especially considering agricultural regions that are not very resilient to climate change.

The situation in Portugal

“In the near future – by the end of the 21st century – Portugal will face a temperature increase around 2.5 to 4º C”, explained Mafalda Pereira, agricultural engineer and researcher at INESC TEC. These changes will impact agricultural and agrarian ecosystems”.

In the beginning of the millennium, a team at the University of Lisbon carried out studies that assessed the impact of climate change on different sectors, including agriculture. The team concluded that the future climate scenario will be hotter and drier. They also stated that, with the exception of grassland and forage, all crops show a reduction in productivity. In other words, the same efforts and agricultural practices will lead to less food. And the problem is that the Portuguese population is increasing. A future scenario with more people and reduced agricultural productivity is likely and worrying in several regions of the country, including the Douro region.

“In the Douro region, the increase of the maximum and minimum temperatures and the periods of extreme drought and untimely rainfall (in June and July) created the conditions necessary to the emergence and spreading of pests and diseases,” explained the researcher.

However, scientists reached an important conclusion: since productivity does not depend exclusively on the weather, farmers can and should adapt to reduce the negative impacts of climate change. One of the adaptation strategies is to get to know crops better — in order to grow them better. This is where the Metbots story begins.

The Metbots

“Today’s climate is not the same it was 20 or 30 years ago. Consequently, we must study how today’s climate influences the plants’ physiology. As soon as we’re able to understand how the plants’ physiology work, we’ll be capable of addressing the challenges and even adopt prevention actions,” said Renan Tosin, agronomist and researcher at INESC TEC.

Renan Tosin is part of a multitalented team that created a mobile platform for the metabolic monitoring of plants and fruits. The small device integrates sensors for spectroscopy measurements, in order to collect information about the plants’ metabolism and physiology. During one of the latest tests, carried out at the Douro region, the technology was placed in a robot that moved autonomously through a vineyard, collecting data.

“Basically, we ‘transported’ the laboratory into the field using a non-intrusive method,” added the researcher at INESC TEC’s Centre for Robotics in Industry and Intelligent Systems (CRIIS).

One of the key analysis parameters to infer the health of grapevines is the water content. The methodology used worldwide is burdensome — farmers often need to collect samples before sunrise — and expensive, making it impossible to map the entire vineyard. According to the researcher, this method resorts to healthy leaves placed in a chamber that presses them until they expel sap. From that moment on, a pressure value is measured to estimate the vine’s water content. Metbots enables the calculation of the water content of the vineyard using a non-destructive strategy.

“Leaf pigments, such as chlorophyll and carotenoids, work as intermediary for the grapevine’s water data. In other words, we can estimate the base water potential by estimating these pigments. Using spectral data collected by Metbots, we’re able to estimate these pigments, and from there calculate the grapevine’s water content. We can also estimate other biotic and abiotic indicators and establish a cause-effect relationship”, explained the researcher.

“The equipment revolutionises this area. With this biological information, we’ll be able to study and understand the influence of agricultural practices and climate change at the plants’ cellular and metabolic level,” added Rui Martins, a researcher at INESC TEC’s Centre for Applied Photonics (CAP) and a member of the Metbots team.

With the support of INESC TEC’s Technology Licensing Office, the Metbots technology is covered by different intellectual property rights at international level, including patents in the main world markets.This enables the dissemination of the technology, while safeguarding the Institute’s interests and promoting collaboration and economic valuation of the R&D efforts and results. However, and for an idea to become a marketable technology, there’s a long road to travel. Towards speeding up this process, the INESC TEC established the TEC4AGRO-FOOD in 2014 – one of the TEC4 initiatives, and a new organisational approach that aims to structure the market-pull innovation process, as opposed to the science-push that occurs naturally at the R&D centres. The Technology Licensing Office and TEC4AGRO-FOOD collaborate to increase the chances of success of certain technologies, transferring them from the institute to society. In this case, the Agro-Food and Forestry take the spotlight.

From seed to commercialisation

At INESC TEC, the great commercialisation opportunities for agri-food and forestry technologies materialise in several ways: via application to traditional funding programmes, through the establishment of partnerships with well-known companies and also by way of lifelong dreams. One day, André Sá, business developer at TEC4AGRO-FOOD, visited the headquarters of ADVID (Association for the Development of Viticulture in the Douro Region), an association of which INESC TEC is a member. There, he met a member of the INIAV (National Institute for Agricultural and Veterinary Research) who was about to retire without fulfilling one of his lifelong dreams.

“I asked him about his dream, and he replied, ‘being able to identify the grape varieties through images, because the only way to do that is through people’s knowledge. There is no technology involved.’ I said ‘Well that’s interesting.’ After that convo, André Sá contacted ADVID – the entity that represents the wine sector – directly, and they claimed that this idea was actually everyone’s dream.”

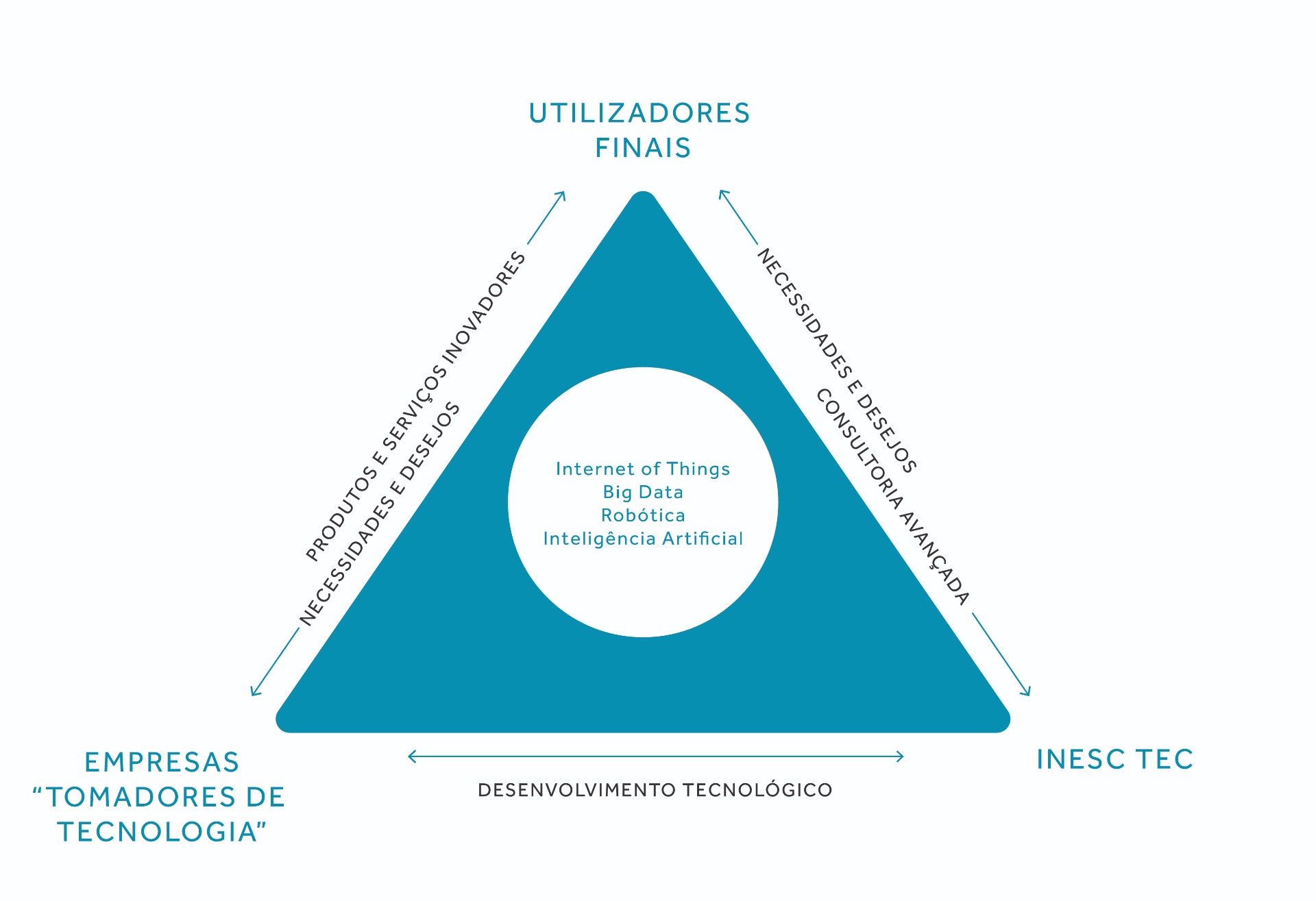

After the conversation, André Sá spoke with an INESC TEC researcher from the field of robotics and Internet of Things, who was sure that the Institute had the technology necessary to address the challenge. The dream could become true, but there was one key element missing – the technology contracting company. “INESC TEC develops prototypes, but it doesn’t provide products or services. Together with the end user, we establish the key needs and aspirations, in order to develop advanced consultancy, but the development of technologies is only possible with the support of technology contracting companies, with whom we complete this innovation triangle” explained the business developer.

The innovation triangle includes the end user, in this case the winegrower or the wine company, the academy (in a broader sense) and technology contracting companies that, together with INESC TEC, develop the technology and later provide the product/service to the end user. “After a few meetings with an artificial intelligence company, I made a phone call. I told the manager that I had something he’d find interesting, since he was eager to get involved in the agro-food and forestry sector. He could be the solution to complete the triangle.”

The dream came true – INCAFO

After the application to a funding programme, the involvement of more partners and the submission of a formal application, the INCAFO – Grape Varieties Identification through Leaves began – benefiting from a budget of +€500K.

As proposed initially, the INCAFO researchers will explore and develop an efficient, economical and accessible tool that winegrowers can use to identify a wide range of grape varieties.

“This would mean a lot to many people. A friend of mine inherited a farm, and he’d love to use a method to identify the grape varieties in his vineyard. If we could point our smartphones in the plants’ direction and identify them qucikly, that would be great”, added André Sá.

“In addition to mobile applications, we will resort to advanced image processing techniques and machine learning as the main technologies of the INCAFO system. These technologies will favour the automation of the grape variety classification process, using the images collected by the mobile application,” added Tatiana Pinho, a researcher at CRIIS.

At the end of the project, the business developer will explore the valorisation of the results. The main objective of INESC TEC’s technology transfer strategy is to prevent prototypes from remaining on the researchers’ shelves, unused. Hence, there are more initiatives that seek to address real-life problems.

Pinpoint precision in agriculture — Smart Fertilizers

In 2018, Herculano, a company specialised in agricultural equipment (cisterns and other tools), focused on developing a smart cistern — one that could apply slurry as a fertiliser according to the absolutely necessary quantity, at the right time and in the right place. To do so, Herculano needed technological support. According to André Sá, the commercial value of the sensors was unreasonable, when compared to the cistern’s value. INESC TEC managed to develop them at a competitive value. This collaboration was obvious, but that wasn’t always the case. “We met several times until Herculano realised that this could be a very rewarding partnership,” he explained.

From the need to create this smart cistern, the Smart Fertilizers project emerged. Researchers applied sensing and automation technology to a cistern, which extracts a spectral signature from the slurry, obtaining an estimate of the amount of each relevant nutrient, e.g., nitrates, phosphorus and potassium. “The main aspect is understanding how much nutrients does a given place need to ensure the crop’s health and reach maximum productivity”, said Filipe Neves dos Santos, researcher at the Centre for Robotics in Industry and Intelligent Systems and project leader. “Rather than a tractor that applies it [slurry] evenly, there’s a machine able to adjust the application rate according to the real needs of a specific location”.

This is a smart precision farming strategy, and the technology is already in the market. “We created a product that is already available. Are there any sales? Not yet, but many farmers have pre-ordered it. The final step is actually seeing farmers using this cistern while working” concluded André Sá. “This is not a short-term process. It’s quite demotivating witnessing projects that do materialise into products and never reach the end users”.

The long struggle to find solutions

There are other disheartening factors that can turn researchers away from technology transfer: in order to submit a patent for certain innovations, they must be kept secret for a while, with said process taking time -aggravated by the missing incentives in terms of assessment processes of researchers who dedicate their time to this cause. There are still obvious differences in mindsets. “Companies and academia have different ways of thinking. Some think mostly about publications and projects, while others think about money”, says André Sá.

As a result, many researchers avoid presenting their findings to the market; according to Bruno Santos, from INESC TEC’s Technology Licensing Office, there are no winners in this situation. “The knowledge and technology transfer must be one of the main missions of an institution like INESC TEC. Intellectual property works as a vital tool that allows people to formalise intangible assets and facilitate their transfer and adoption by the industry, so that the knowledge generated can reach its maximum impact.”

“I am an advocate of merging technology with agriculture. I believe that this approach provides (and will provide) a lot of potential to leverage current agricultural practices,” added Mafalda Pereira. “By resorting to adequate techniques (combining software, systems and equipment), it’s possible to generate and analyse large volumes of data, thus making the producers’ tasks more agile, autonomous and integrated”.

Ideally, in the distant or near future, both engineers and farmers will keep being valuable, strengthening said value through collaboration and innovation. If feeding all people on Earth in 2050 requires a massive increase in food production, then humanity cannot afford to leave innovation on the shelf.

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!

News, current topics, curiosities and so much more about INESC TEC and its community!